Vertigo

Flowchart

RED FLAGS REQUIRING URGENT ENT REFERRAL

Associated facial nerve palsy

Neurological signs may suggest an acoustic neuroma and require urgent (non-cancer) reveiew

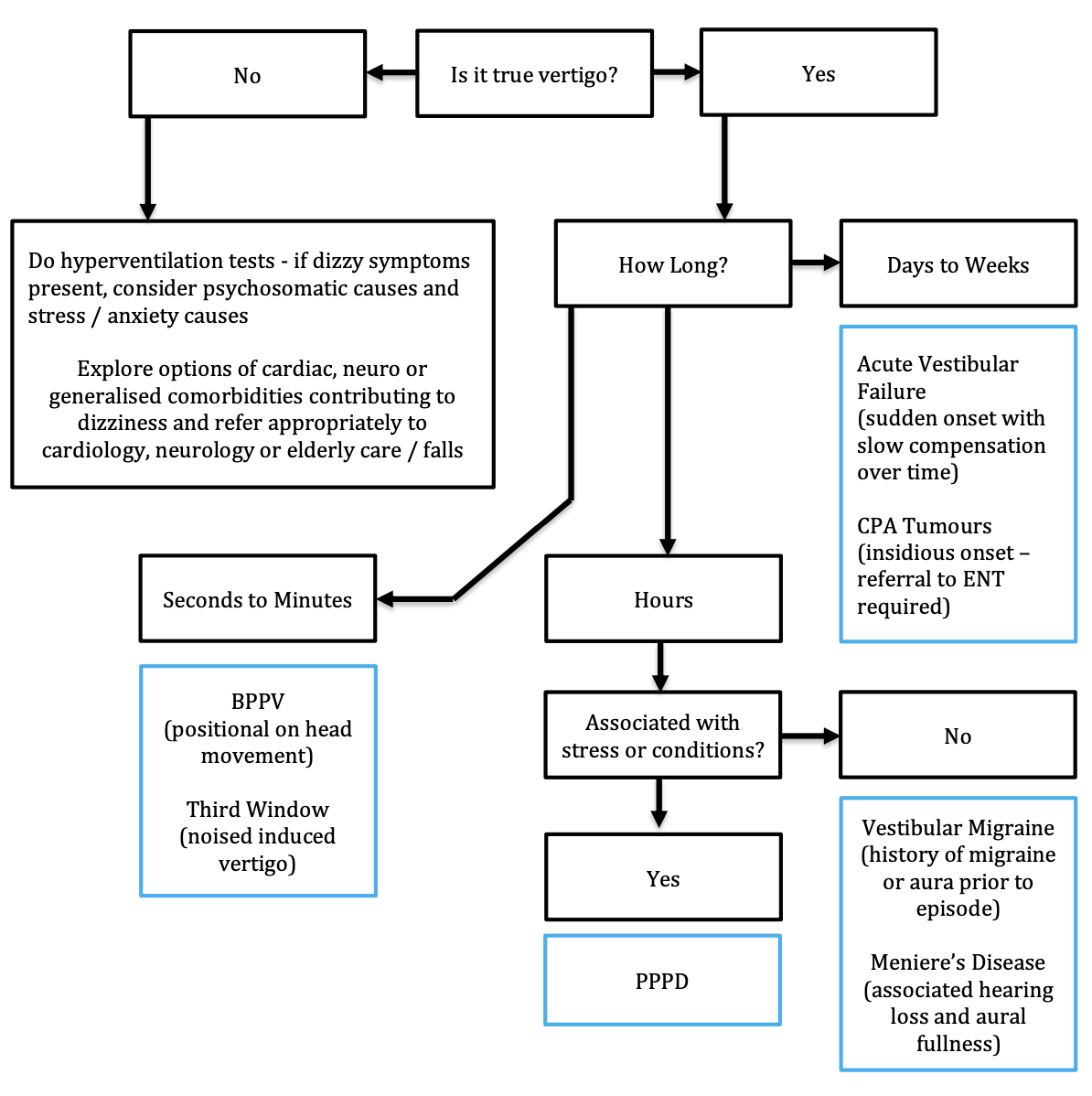

Apart from establishing a diagnosis, differentiating between the various types of dizzy symptoms can help channel referrals to the right specialties. ENT deals with vertiginous symptoms (illusion of movement, often rotatory), while cardiac and neurological symptoms may need attention from the relevant specialties. Elderly patients at risk of falling from poor balance will gain the best input from an elderly care physician / falls service.

ASSESSMENT AND RECOGNITION

History

Is this actually vertigo - an illusion of movement? If not, consider non-ENT causes.

When did it first start and what triggered it?

How long does the vertigo last for? (It is the length of the actual vertigo episode that is important, not other symptoms such as lethargy/muzziness)

What makes it better? (rest, dark room implies migraine)

Before the vertigo started, was there an aura / premonition of it coming on?

Does the vertigo start on moving your head / turning over in bed? (Suggestive of BPPV)

How often do the episodes occur, and is each episode the same?

Was it associated with any headaches, flashing lists, zigzag lines, nausea or vomiting? (Suggestive of vestibular migraine)

Was it preceded by a heightened tinnitus, ear fullness or hearing loss? (suggestive of Meniere's)

During the episode, did you have any loss of consciousness, chest pain, palpitations, loss of muscle power or coordination?

Do you have any visual problems. Have you had it checked recently?

Do you suffer from migraines or any headaches that are worse when you lie down?

Do you have any hearing loss, tinnitus, ear pain or discharge?

Relevant past medical history (including peripheral limb disorders and neuropathy)

Full medication history (check the BNF as many medications cause vertigo as a side effect)

Occupation and driving history

Social circumstances including mobility aids, coping mechanisms at home.

Examination

Otoscopy

Cranial nerve examination (especially eye movements looking for nystagmus)

Cerebellar and gait examination

Neuro examination

Dix-Hallpike test (to diagnose BPPV)

* HINTS exam is helpful to distinguish vestibular failure from a stroke

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND PRIMARY CARE MANAGEMENT

Generally, the timing/duration of the vertigo can give a good idea about the likely diagnoses.

Seconds-minutes

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) - Patients experience vertigo that comes on with head positional changes (classically turning in bed). The actual vertigo only lasts for 30 seconds to a minute but the patient may feel muzzy headed for a few hours after. The condition is generally self-limiting as the particles get reposition on their own in due course. A Dix-Hallpike test is diagnostic for classical posterior-canal BPPV, with geotropic nystagmus indicating a positive test. An Epley manoeuvre is curative in 80% of the cases and can be safely performed in a general practice setting. Patients should be given a Brandt-Daroff exercises leaflet to perform at home and the Epley can be repeated in due course if the condition is not completely cured. Refer to ENT / audiovestibular medicine if not improving over time. Do not start medication for suspected BPPV.

Superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome - this is rare. Bone covering the superior semicircular canal gets resorbed or is poorly formed. These patients experience brief moments of vertigo in the presence of loud noise or when external pressure is applied to their external ear. They can also describe hearing internal sounds like eye movements, swallowing and breathing. Refer routinely to ENT.

Hours

Vestibular migraine - this is common and under-diagnosed. Sufferers have episodes of vertigo which are often different each time (unlike Meniere’s disease). Some may have a history of classical migraine, but commonly there is no clear association with headache. The vertigo may be preceded by an aura (visual or auditory) as well as symptoms of nausea, lethargy, photophobia and phonophobia. The attacks are debilitating and would usually result in the patient having to sleep it off in a dark room (akin to classical migraines). Acute episodes can be helped with triptans or prochlorperazine. Refer to neurology when suspected, especially if requiring prophylactic treatment.

For more info, please click here

Persistent postural perceptual dizziness (PPPD) - This is a relatively new neuropsychiatric diagnosis typified by chronic subjective dizziness, phobic postural vertigo and related disorders, associated with a lot of stress and triggered by crowded environments, stressful circumstances and confusing visual cues (eg. zig-zag lines on a carpet). Diagnosis is based on the Barany society diagnostic criteria and treatment is centred around education, distraction techniques and cognitive behavioural therapy.

Meniere's disease (MD) - this is quite rare and over-diagnosed. The classical triad is episodic vertigo, hearing loss and tinnitus / aural pressure. Episodes are the same every time (unlike migraine). Betahistine, which has been traditionally used to treat Meniere’s, has been shown to have a placebo effect only (https://www.bmj.com/content/352/bmj.h6816). Patients with suspected MD ought to be asked to restrict salt and caffeine diet, to keep a diary of their vertigo attacks and be referred to ENT/Otology. Intratympanic injections and rarely surgery can be required. Treat vertigo attacks with prochlorperazine (not regularly).

Days - weeks

Acute vestibular failure - also known as acute labyrinthitis or vestibular neuronitis; essentially a collapse of the vestibular system from inflammatory, infective, vascular or commonly idiopathic insults. The patient has severe vertigo and nausea lasting days. The usually have horizontal nystagmus worse on the affected side, and a positive head impulse test. The HINTS exam is useful is ruling out a stroke. The condition is almost always self-limiting with things starting to improve after a week and normal function attained after 3-6 months. Prescribe 7-10 days of prochlorperazine and ask the patient to perform Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises. Patients who show no signs of improvement after 2 weeks can be referred to ENT routinely

Vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma) - benign, slow-growing tumours that impinge on the vestibulocochlear nerve and can cause unilateral hearing loss, tinnitus and occasionally dizziness. An MRI IAM is diagnostic and the majority of patients have a slow- or non-growing tumour, which can be monitored using serial scanning. Sometimes, stereotactic radiotherapy and open surgery are recommended. Refer routinely to Otology/ENT if suspected.

REFERRAL PATHWAYS TO ENT

Same day

Associated facial nerve palsy

Cancer pathway

None (vestibular schwannomas are not cancers)

ENT emergency clinic

None

Routine

Recurrent / non-responding BPPV patients

Suspected third window syndrome

Suspected Meniere's disease

Suspected cerebellopontine angle tumour

Non-improving acute vestibular failure

Suspected vestibular migraine (to neurology)

Author: Mr Ananth Vijendren BM MRCS MRCS (ENT) FRCS (ORL-HNS) PhD, Consultant Otologist/ENT Surgeon, Lister Hospital, Stevenage